An American tragedy is playing out in many school districts across the nation.

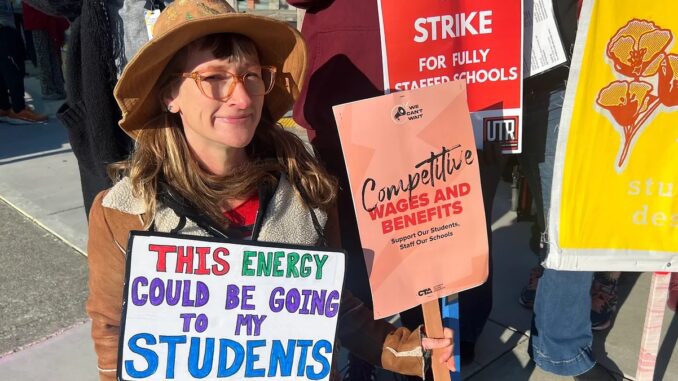

I witnessed it close at hand in the final weeks of 2025 when I covered the teachers’ strike in West Contra Costa Unified, a school district in the San Francisco Bay serving 25,000 students, two thirds of whom live in low-income households.

It was the first teachers’ strike in California, and only the second in the U.S., during the current school year.

In 2026, expect to see similar conflicts not only in neighboring districts, but in others around California and the nation. Teachers’ unions in some of the largest school districts in California, including Los Angeles Unified, San Francisco and Oakland — have declared an impasse in negotiations, along with threats of possible strikes.

In the West Contra Costa district, which includes the city of Richmond, teachers “won” the strike by getting a pay increase of 8 percent over the next two years — 2 percent less than what they were demanding — along with improved health and other benefits.

But even with the pay increase, teachers will still earn a salary that will fall far short of what many, if not most, will need to live in the district where they teach, and almost certainly not without the help of another high income earner in their family. As for owning a home — forget about it.

The salaries of beginning teachers with full credentials in the West Contra Costa district will go up from just over $58,000 to about $63,000. That’s what new teachers earn in one of the most expensive metropolitan areas in the nation — after spending four years getting a bachelor’s degree and as many as two years in a post-graduate teacher credentialing program.

The wages of the highest paid and most experienced teachers — those who have worked in the district for 27 years or more and have earned multiple post graduate course credits or advanced degrees — will increase from $119,000 at the top of the salary scale by another $10,000.

Financial plight

It is, however, a mystery how the district, which is already struggling to avert insolvency, will be able to pay for these increases. District administrators say they will have to come up with an additional $105 million over the next three years to pay for what it has just agreed to at the bargaining table. That will be on top of a hefty structural deficit the district is already grappling with.

For the past several years, the district has been spending more than it is receiving from the state by millions of dollars, as a result of multiple factors. These include declining enrollments due to lower birth rates, soaring costs of special education, and a surge in charter school enrollments, which means less revenue for district schools.

In fact, the strike settlement — which includes similar raises for non-teaching staff — makes the district’s financial plight even more perilous.

For West Contra Costa, the risk of insolvency is not a theoretical one. In 1991, it was the first in California to have to get a bailout loan from the state to avoid bankruptcy. It has been on shaky financial ground almost continuously since then, not helped by management and board dysfunction at various points along the way.

What seemed to get lost in the labor dispute is that school districts aren’t profit making institutions. In California, district budgets are determined almost entirely by what they get from the state’s general fund, based largely on the number of students in attendance each day.

The only way the West Contra Costa district has been able to balance its budget has been by making extensive budget cuts and drawing on a special reserve it was required by the state to create when it received its $29 billion bailout loan three decades ago.

But that reserve will be completely exhausted at the end of next year — despite assertions from teachers, parents and others that the district has a hidden reserve.

How is it that people doing one of the most important jobs in the United States are fighting over what effectively are pennies when compared to the billions of dollars being raked in by hedge fund managers, venture capitalists, bitcoin investors, and corporate CEOs?

The same dynamic is being played out in school districts across the nation, as working Americans struggle to cope with rising costs of living that are irrelevant to the highest income earners.

Teachers vs. teachers

Deepening this tragedy is that those on either side of the bargaining table are invariably teachers by profession.

Local union presidents are typically teachers who have left their jobs temporarily to lead their unions. Usually they’re joined at the bargaining table by other union members who are still active classroom teachers, counselors, or librarians.

Across the table are school superintendents and business managers who more often than not are veteran teachers who have moved into administrative positions.

Yet administrators are typically portrayed as heartless bureaucrats who don’t care about children and who are exaggerating a district’s financial problems or blatantly lying about them.

In West Contra Costa, that narrative seemed hard to square with the life stories of the people running the district. School Superintendent Cheryl Cotton, who only assumed her post in July, has multigenerational roots in the district. Her grandfather migrated to Richmond from Arkansas as part of the Great Migration in the 1940s to Richmond to work in the Kaiser shipyards that built Liberty ships which helped win World War II.

Cotton’s mother was a teacher who taught in the district for 42 years (and was Cotton’s first grade teacher in 1978). Cotton also became a teacher and was a principal and administrator for many years in the district where she — and her parents — still live.

She just returned six months ago to head the district, after serving as deputy superintendent for the entire state for the past three years.

Kim Moses, the district’s business manager, and Cotton’s second in command, was also born and raised in Richmond, and similarly graduated from its schools, in the same year as Cotton. She too was a teacher in nearby Oakland for a dozen years, where she participated in a drawn-out teachers’ strike in 1995. She returned to her home district where she served as a principal for 15 years.

Last year, she was the interim superintendent, and was able to edge the district away from the precipice of insolvency when its budget earned a “positive certification” from oversight agencies for the first time in years.

‘You can’t give what you don’t have’

What’s notable is that both union and district negotiators agree that teachers and other school staff should be paid more generously. “We all agree that they deserve more, but you can’t give more than you have,” Moses told me a few days before the strike.

Both sides also argue that the state should put up more money to underwrite education. But California already spends about 40% of its general fund revenues on its schools, as it is required to do by an initiative approved by voters in 1988.

It is hard to imagine how the state, which is itself facing massive budget deficits, could spend an even larger share of its revenues on its schools — without pitting schools and teachers against multiple other equally deserving services or programs.

Teachers and other school staff are understandably angry at being told they have the most important job in America, but that there just isn’t the money to support them at a level proportionate not only to their qualifications, but to their purported value to American society.

No bail out for teachers?

At the same time teachers were on strike in West Contra Costa for a $3,000 annual pay increase, and being told the district didn’t have that kind of money, President Trump was able to come up with $12 billion to bail out soybean farmers as a result of his impulsive and irrational tariff policies.

He also launched a campaign to recruit 10,000 new ICE agents—with multiple incentives such as offering $50,000 in signing bonuses, paying off up to $60,000 of applicants’ student loans, and enticing retirees to return to ICE by allowing them to earn a salary on top of their existing pensions.

Teachers might rightfully ask why the federal government couldn’t establish a $12 billion fund to bail out struggling school districts. Or launch a campaign to recruit 10,000 new teachers by offering them $50,000 bonuses and paying off their student loans.

Or perhaps the nearly one thousand billionaires in the United States could pledge a tiny fraction of their billions for a fund to support teachers?

These are fantasies, of course. “We ask teachers to be everything, but as a society have not paid them anything near to what we expect of them,” said Michael Fine, CEO of the Fiscal Crisis Management AssistanceTeam, a California watchdog agency set up to help school districts avoid bankruptcy.

Fine told me that school districts’ costs on basics such as liability insurance, health benefits, and utilities, are rising at a faster rate than the cost of living increases they receive from the state. Nor can districts count on revenues rising as they could for the last half century as school enrollments climbed along with population growth. Now just the reverse is happening.

Teachers, too, must contend with rising costs — and somehow manage on salaries that are lower than those of college graduates with comparable qualifications.

”We place tremendous responsibilities on the backs of teachers,” Fine said. “Ultimately we have to figure out a cost structure to support them to take those on.”

So far, as a society, we are nowhere close to doing that.

Be the first to comment